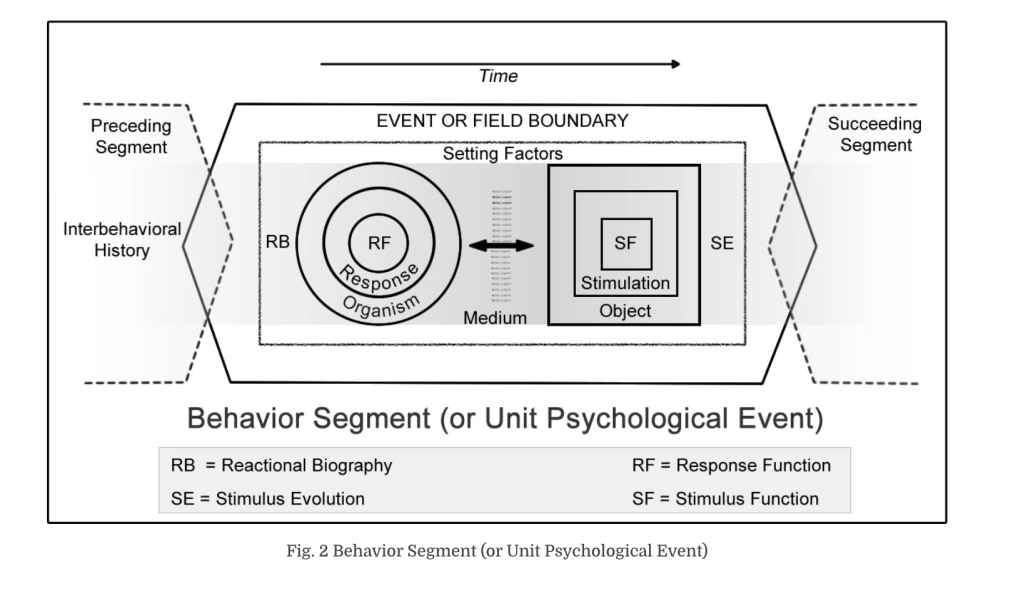

For my next trick, I will attempt to unpack this diagram which was the invention of a man called Jacob Robert Kantor (1888-1984). It represents something called the Interbehavioral Field and is the cornerstone of Interbehaviorism (I’m using the US spelling because that’s where the ideas come from). Interbehaviorism gives us a new way of conceptualising the relationship between the human organism and its context.

Interbehaviorism never really took off during Kantor’s lifetime but is starting to take off now. There are lots of people who are contributing to this but I am going to single out two incredible women: Dr Linda J Hayes and Dr Emily Sandoz.

Dr Hayes, together with Dr Mitch Fryling, recently published Interbehaviorism: A Comprehensive Guide to the Foundations of Kantor’s Theory and Its Applications for Modern Behaviour Analysis. What you get from me is going to be, I hope, something that someone without any knowledge of behaviourism could get their heads round. But I am not an expert. If, after you read these pages, you are looking for a next step, this book is it. Hayes knew and worked with Kantor, and has done much, since he died, to preserve his legacy during an era which was disposed to dismiss his work as too difficult and / or insufficiently pragmatic.

Dr Sandoz has done a huge amount to pioneer the real-world applications of interbehaviorism, particularly in the area of talking therapy. It is a pleasure to acknowledge her work here because I owe her an enormous debt. It is currently my privilege to be able to meet with her remotely once a month and this association has transformed my life.

Behaviour Segment (or Unit Psychological Event)

Back to the diagram. Let’s start with the Behaviour Segment (or Unit Psychological Event), which is the hexagonally shaped thing and everything it contains. Very simply, this refers to any experience we have or, to put it another way, anything that a human being does. So, let’s say that, for the sake of argument, I am – right now – stroking my beard. This is something I do quite a lot. We can consider this beard stroking, the particular chunk of beard stroking that I am engaged in right now, as a behaviour segment. When I say ‘we can consider’ this as a behaviour segment rather than ‘this is’ a behaviour segment I am doing that on purpose to make a small but important point. From the moment we are born to the moment we die, we are continuously doing stuff, continuously behaving. This behaviour does not arrive in the world in little separate chunks of doingness, so although it is true that this beard stroking is, to use Kantorian language, a distinct ‘natural event’ in the sense that we can directly observe it start and stop, it has a beginning and an end, a birth and a death, it is also true that this event, in so far as we conceive of it as a separate thing that we can detach from its surrounding context for the purpose of analysis, is a ‘construct’, something that we have created by making it our specific focus. If you want a visual analogy for this distinct and yet not separate ‘natural event’ think of a whirlpool.

The one-off event which is a whirlpool springs into existence when a particular set of circumstances arises that make this whirlpool’s emergence inevitable. There will be other whirlpools in the future that look similar but they will not be identical to it because like every other natural event this whirlpool is unique. It bursts into existence and then it disappears, distinct but not separate from its context. There is no gap between the whirlpool and the water in which it arises. You could say that the whirlpool is an instance of relating, an instance of the water relating in a particular way to itself. This particular piece of beard stroking that I am engaged in is like that whirlpool; its distinct existence is the observable embodiment of a particular relationship of the interbehavioral field to itself.

A digression on the behavioural stream…

I shall digress a little here to introduce a useful concept that does not belong to the diagram: the behavioural stream. Dr Sandoz talks very compellingly about this. As I stroke my beard, there are lots of other things that I am also up to: my heart is beating, my non-beard-stroking-hand is resting on the keyboard of my laptop, I am thinking about what to write next etc…this list could probably expand infinitely and comprises what we can refer to as ‘the behavioural stream’ which means all the behaviours the human organism that is me is engaging in at this particular moment. You might notice that I am using ‘behaviour’ in a particular way here. In this piece, behaviour just means anything that a human organism does. We do not have to be doing something on purpose in order for it to be behaviour. We do not need to be moving our body in a way that is easily publicly observable either; thinking, feeling, remembering, these are all bits of behaviour, according to this definition. To be considered to be behaving, you just need to be alive. You might not feel as though you are doing much right now but from this perspective you are doing a potentially infinite number of things all the time. So, give yourself some credit! Don’t let me hear you saying ‘I did fuck all today’ ever again! For one thing it feels terrible to see you lay into yourself like that but, for another thing, and more relevantly, as far as this perspective is concerned, it is just not accurate. You are always behaving right up to the moment when you die. End of digression.

Behaviour Segment (or Unit Psychological Event) continued…

So, although we have chosen to focus on the behaviour segment that demarcates ‘the beard stroking that Jacob is engaged in at the moment’, we could have selected any other event occurring in the entire behavioural stream. For something to be a behaviour segment or Unit Psychological Event, we just need to be able to point to a specific behaviour the organism is doing for a chunk of time. It needs to start and then stop like a whirlpool. So that’s Behaviour segment ticked off. It’s just any specific thing we do.

Event or field boundary

Next up, ‘event or field boundary’ which on the diagram refers to the outline of the hexagonally shaped thing in the middle. So, right now I am stroking my beard, and at some point I will stop doing that, and then we will have reached the ‘event or field boundary’ where, like the whirlpool, this particular instance of beard stroking will be at an end never to be repeated again. So this label simply indicates the limit beyond which this bit of beard stroking is no longer taking place, it’s become ‘a thing of the past’. Although I may engage in the generic activity of beard stroking again, just like other whirlpools may arise, this bit of beard stroking that I am currently engaged in will never happen again, it is unrepeatable and irreversible. We have already touched on this a little bit but it is worth pausing here for a moment because it is pretty important. It is important to understand that interbehaviorism is interested in uniqueness.

A pause to ponder uniqueness…

Interbehavioral psychology is interested, specifically, in the uniqueness of every single ‘unit psychological event’, every single thing we do, every instance of beard-stroking, or of anything else. In this respect Kantor has something in common with Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher, who famously said (roughly) ‘a human being never steps in the same river twice’. As you probably know, all he meant by this was that the next time the human being steps in what (in another sense) is the same river both he and the river will be changed. He might be changed in lots of ways, time has passed between the first and the second step, he might have experienced a terrible tragedy and be approaching the river as a sadder wiser man, but here we are interested in something more subtle and more certain…we are interested in a way in which he must be changed, namely in the sense that, the next time round, he will be approaching the river as a man who has already stepped in this river once and this will change his experience of the river; he will expect some things – the experience of wetness for instance – based on his previous experience of the river. The river too might be changed in lots of different ways, time has passed for it too, someone might have dumped a load of human waste in it, killing half of its wildlife, but here, because we are not trying to understand the experience of being a river (we would have to be a river to do that) but the experience of being a human being stepping into a river for the second time, that is not the change we are focussed on. We are focussed on the way in which the stimulus, which just means anything an organism can respond to (here the stimulus is the river, earlier on the stimulus was my beard), has changed; the river, is now ‘the river that this human being has already stepped in once before’ and the human being, at the risk of labouring the point, is ‘the human being that has already stepped in the river once before’. This might feel as though we are just saying the ‘same thing’ in two different ways and, in a way we are, but let’s not get too caught up in that, I think we are now ready to move onto the juice: RF and SF, response function and stimulus function and the closely related terms: response, organism & stimulation, object. This is where, for me, things start to get really mind-bendy because we’re in the realms of simultaneity which does funny things to our everyday understanding of time. Excited? Good! Me too!

Response Function (RF) (+ Organism +Response) x Stimulus Function (SF) (+ Object+ Stimulation).

The word ‘function’ gets used in all sorts of ways which is bothersome. Here this word is being used to help us distinguish between form (or to use a more fancy word ‘topography’) and function. Form, or topography, just means what something looks like on the surface as opposed to what it is doing. To put it a little more technically topography refers to the way a particular thing occupies space. So right now the stroking ‘response’ that I, as a whole organism, am engaged in with respect to the stimulating object, that is my beard, is occupying space in a particular way that looks like this:

Knowing this tells us a bit but not much about the unrepeatable, irreversible, unique psychological event that this instance of beard stroking is. Function refers to the reciprocal relationship in which stimulus and response participate. To put it another way, it refers to everything that is brought into existence by the interaction of stimulus and response. As with the stepping into the Heraclitean River, so with the stroking of my beard, the functional relationship between stimulus object (i.e. my beard) and organismic response (i.e. my hand reaching out and stroking) is constantly evolving. Without attempting to exhaust the rich functions of this interaction, I can tell you that when my hand and beard came together to create this magical behaviour segment a few things sprung into existence in addition to what you can easily observe: I was reminded of my late father who also wore a beard that he regularly stroked and I also felt the familiar and not unpleasant sensation of my fingertips touching my beard hair, as well as the slightly less pleasant sensation of my beard hair tugging a bit at the skin of my face. That feels like just scratching the surface (no pun intended) but you get the idea. So, we could say that as well as evoking some physical sensations, one of the stimulus functions of my beard, as I stroked it, was, on this occasion, and likely other occasions, to remind me of my father. This is an example of something called ‘stimulus substitution’ which is quite a big deal.

A bit about stimulus substitution…

‘Stimulus substitution’ is a term for the phenomenon whereby a present stimulus shares functions with a stimulus which is absent, even though both stimuli may have quite different topographies (i.e. even though they look different). To put this in layman’s terms, stimulus substitution is at play whenever we respond to a thing as if it were something else. So in this case, the stimulus of my beard being stroked shared functions with my absent father; it evoked a response similar in some ways to the response that his actual presence would evoke. Stimuli come to acquire the same functions as stimuli with different topographies when both stimuli occur together in space-time. As a responding organism, I had lots of experiences earlier in my life when my dad’s beard and my dad showed up at the same time (!), and as a result, the sight of a beard, came to share some functions with dad; that is to say, these things came to evoke a similar response in the organism that is me, to the response evoked by the actual live presence of my dad. Stimulus substitution is an enormous part of how we experience the world thanks to the invention of language. Words are stimuli that almost always function as a substitute for something that is absent. For example if I say, ‘I have a cat’, provided that you speak English and are familiar with the word cat and what it usually refers to, you will respond to this word not in terms of its actual properties (i.e. you will not respond to it in terms of the changes in air pressure caused by my utterance of the word ‘cat’ or what it looks like as pixels on a screen) but in terms of your learning history with respect to the furry animals who, in your experience, have been associated with that word. It’s inevitable, because two individuals will always have at least slightly different learning histories with respect to any given stimulus, that your idea of a cat will be slightly different from mine but also likely that it will be some idea or image of a cat that is evoked for you by my statement rather than an aesthetic appreciation of the sensory qualities of my speech act, or the physical appearance of the word wherever you are reading it.

Response Function (RF) (+ Organism +Response) x Stimulus Function (SF) (+ Object+ Stimulation) continued…

It will, maybe, have occurred to you as you read this – thank you so much for staying with me! – that stimulus and response functions are impossible to prise apart. I mean, clearly, my beard is not the same thing as my hand, their topographies are quite distinct. Indeed my beard and my hand for the most part lead quite separate lives. My beard, for instance, spends large swathes of time doing things other than stimulating a stroking response from my hand and my hand responds to stimulus objects other than my beard all the time: knives and forks, pens, computers, tennis rackets, the silky fur of our family cat Flopsy etc…But once my beard becomes the stimulus for a beard-stroking response from my hand, once it acquires this function, then stimulus and response are not only inseparable, they are also simultaneous. There is not some kind of linear causal sequence where the stimulus is followed by a response, stimulus and response form an interdependent unity. They are not two things, they are one thing – an interaction.

It’s the end of causality as we know it…

I think this merits another digression because I know that the first time I encountered the idea that stimulus does not precede response I felt like my brain was going to explode. It occurred to me that if stimulus does not precede response then nor does cause precede effect and this is fundamentally at odds with the way we are all usually taught to think about the world. But how can cause not precede effect? Well let’s imagine that Mr A shoves Mr B in the back with his right hand resulting in Mr B moving a bit. Clearly the push comes first and the movement follows, right? Cause and effect, plain and simple. But look what happens if you slow things down here. If you slow things right down so that you can observe the actual moment when the right hand of Mr A is applied to the back of Mr B, you can see that there can be no temporal gap between the pushing and the moving; as soon as the pushing starts, as soon as stimulation is afoot, responding is also occurring. They are interdependent aspects of a single unitary event, given different names for the purpose of analysis, but not ‘really’ separate in any way. The same can be said for whatever it was that ’caused’ Mr A to shove Mr B in the back, and whatever it was that ’caused’ that and so and so on forever. I say ‘forever’ because, according to this perspective, there are no ultimate causes, no external causes that are somehow outside of everything else, giving everything a push to get things started. There can be no ultimate causes because there are no separate things. There can be no gap between an organism and its context, no space in which there is no context, context and organism must constantly be in contact and so are not separate but connected. And if there are no separate things then it means that, in reality, there is only one thing which is everything, past, present and future, everywhere all at once. This seems very hard to comprehend because of the astonishing variety that clearly does exist. The one infinite thing which is everything is not just an amorphous, undifferentiated blob, it is a breathtakingly, beautifully, terrifyingly complex field that comprises an ever-expanding number of things, or events, which, although not separate, in the sense that they are always interacting with, transforming and being transformed by their context (i.e. by each other) are also, each one of them, completely unique and, in that sense, distinct. It is the idea of temporal and spatial separateness that we have got rather hung up on, particularly in the West and, as with everything else, there’s a history to that, but not a history that leads us to some ultimate cause. Just because it’s all connected, all one, does not mean that it is all the same, does not mean we have to give up on difference and unique individuality. Nor does it mean that we have to give up on exploring and learning but we might want to stop doing this in a way that is driven by a fantasy that this exploring and learning will at some point be complete because we will know the entire truth and be able bend the universe to our will in a linear, cause-and-effect way. In place of this we might want to try something more pragmatic that is more like seeing every encounter with some new aspect of the world, especially every new person, but why not also every single thing, as the beginning of a new relationship, an opportunity to gradually become more intimately acquainted with this thing’s idiosyncrasies, as the beginning of a series of iterations, through which your relationship will become progressively more complex, more rich, more mutually rewarding – a bit like getting better and better at dancing with a new partner. Wow! Apologies, I think I may have got a little carried away. If you have followed me and my meandering words thus far, that is miraculous, thank you for your efforts! Maybe go and have a lie down or a cheese sandwich or a pee if you have been holding one in. A pee is definitely next on the agenda for me. Too much information? Sorry, bit of an over-sharer (and there’s a history to that but no ultimate causes).

Setting Factors

Tired of me stroking my beard yet? I am a little bit tired of it, if I am honest; my hand is starting to ache just a little bit, but I want to see this thing through. My friend Fergus said he was interested in seeing this diagram explained and he’s a terrific person, so if for no other reason than to satisfy his curiosity I shall keep plodding on. This psychological event, this beard stroking, that is our focus takes place in a particular situation composed of many factors and these are referred to as setting factors. I am stroking my beard sitting on a chair in a room opposite my laptop and all these objects have stimulus functions that arise not only because of their object properties but also because of my history with them; for example, I can see the chair is made of a green material and it feels firm as I sit on it right now (functions arising directly from object properties), it also reminds me of the old chair that was far less comfortable and made my back ache (functions arising via substitution, like my beard reminding me of my bearded dad). Setting factors are not limited to things in the environment in which the organism is behaving; they also include the state the organism is in (e.g. as I stroke my beard I am also feeling tired, a bit sweaty, excited…). Setting factors are not the focus of the particular event we are focussing on but without them being just as they are, the event would be different – in this sense, they too are part of the event. We can say these factors ‘participate’ in the interbehavioral field.

Medium of Contact

This element of the diagram feels a bit different from the others to me but I am not suggesting it should feel that way to you too. When I think about ‘medium of contact’ I start feeling as though I am giving myself a very basic science lesson and that we have left the world of psychology behind. Media of contact are factors that enable us to interact with stimuli. When I see my niece, Sally, light enables me to see her, and sound waves enable me to hear her when she speaks. When I stroke my beard, the main medium of contact is my body. So, that’s that. As you can see, the medium of contact has to do mainly with direct interactions with stimuli rather than substitute stimulus functions.

Interbehavioural History (RB = Reactional Biography, SE = Stimulus Evolution)

So, let’s get back to, yep, you, perhaps with a slightly weary sigh, guessed it, back to me stroking my beard. When I have finished this piece, stroking my beard will never be quite the same again! To those intrepid intellectual warriors who are still keeping me company at this point, I thank you from the bottom of my heart which is like a very deep well, so that’s from a long way down that I am thanking you. Maybe I should do this as a podcast? Would that make it easier to digest? All good questions but for now I seem to be blogging. On we go. These three phrases – Interbehavioural History, Reactional Biography and Stimulus Evolution – belong together. We’re back in Heraclitus territory here. Every time I respond to my beard (stimulus) by stroking it with my hand (response) I am adding to the history of how I have responded to this thing (reactional biography) and also adding simultaneously to the responses that this thing has evoked from me (stimulus evolution). Each behaviour segment of beard stroking is unique because it builds on what was done before; it’s impossible to for me to stroke my beard for the first time twice, and so with each stroke of my beard, my interbehavioural history with respect beard stroking changes just a little bit, there’s one more functional layer echoing into the present. This is very different from saying that the past causes the present, which relies again on the idea of separateness according to which the past is external to and divided off from the present in some way. I am going to labour the point a little here because I think it is important. The idea of ‘practice’ is maybe helpful here. It might seem odd to talk about ‘practicing’ stroking a beard because this it isn’t something like playing a musical instrument where we might be engaging in an activity with the intention of getting better at it. But if we think about this kind of deliberately engaged in practice, it’s easy to see how the past stimulus-response functions of whatever thing we are practicing are present each time we engage in this activity, each time the organism interacts with the relevant part of context. If I am learning to play the piano, each time I sit down to play, the thing I then do will be informed by all the previous occasions when I sat down at the piano to play. That does not mean that I necessarily remember all or, indeed, any of these previous occasions just that what I do next could not be exactly what it will be without all those previous pieces of behaviours having occurred in just the way they occurred, and in that sense those previous pieces of behaviour are present, they are, functionally, part of the current psychological event. The extent to which we might be aware of this process varies depending on the level of intentionality available to us in any given moment, the extent to which we are knowingly and purposefully engaged in a behaviour. A musician practicing their instrument might have quite a keen sense of how each time they practice is subtly adding to the refinement of their skill. When I am stroking my beard I am generally thinking about something else entirely, so I have very little awareness of what’s going on. But this level of awareness does not alter the process whereby each time we interact, or to use Kantorian language, each time we ‘interbehave’ with a stimulus, a bit of the world (a piano, a beard), we can only do this by building on our previous interactions with that stimulus which, in that sense, never go away. Maybe our awareness of the presence of our interbehavioural history is likely to be greater when there is some discontinuity in our history with a particular stimulus. Maybe we haven’t seen our niece, Sally, in a long time. The stimulus functions that Sally has for us have continued to evolve gradually in her absence via stimulus substitution; we have remembered her, maybe talked about her fondly, sent her birthday presents. But then we see her in person and she’s grown half a metre taller and become a self-conscious teenager. The presence of our interbehavioural history with Sally in this moment adds a surprise reaction to the stimulus functions she has for us and we make her cringe by saying something like ‘My how you’ve grown!’ There’s something rather wonderful to me about this concept of interbehavioural history, the idea that, functionally, the past is always present. It is possible to dismiss intellectually as obvious, a kind of a ‘so what?’ But why would you want to do that, I wonder? My dad (and a whole lot of other people) is (are) dead. There is an obvious sense in which nothing can bring him (them) back. But in another very real sense, no experience that I will ever have could be the experience that it is without all the interactions I had (and that I continue to have) with the stimulus that is ‘dad’; he is and always will be, functionally, present. Rather than thinking about this as a concept, I like to practice feeling it, feeling how the present functions as it does because of everything that has happened up until this moment. My poem ‘Who Built The Rotting Wooden Posts?’ is inspired by some feeling I did in this direction while recalling a lovely walk along a beech in Cromer on the Norfolk coast in the UK. You don’t need to be aware of all the things that have ever happened for it to be true that nothing you ever do could have been just as it is without all those things having happened just the way they happened too. It makes me want to become more aware. It makes me want to know more of the history that has led to the enormous privilege that I have inherited without having done anything in particular to deserve it. It makes me want to do what I can – what can we do? – to act with as much intentionality and awareness as I can. Because whether I act with intentionality or not, whether you act with intentionality or not, for good or ill, our interactions with the world will be present forever. Best try to make the best of it, I suppose? Doesn’t that phrase take on a greater depth of meaning in the context of all of this. For me it does.

So, that’s it, the interbehavioural field. Beautiful, ain’t it?